"On your marks!" A hush falls as 60,000 pairs of eyes are fixed on eight of the fastest men on earth. The date is August 22, 1999, and the runners are crouched at the starting line of the 100-meter final at the track-and-field world championships in Seville, Spain.

"Get set!" The crack of the gun echoes in the warm evening air, and the crowd roars as the competitors leap from their blocks. Just 9.80 seconds later the winner streaks past the finish line. On this particular day, it is Maurice Greene, a 25-year-old athlete from Los Angeles.

Why, we might ask, is Maurice Greene, and not Bruny Surin of Canada, who finished second, the fastest man on earth? After all, both men have trained incessantly for this moment for years, maintaining an ascetic regimen based on exercise, rest, a strict diet and little else. The answer, of course, is a complex one, touching on myriad small details such as the athletes' mental outlook on race day and even the design of their running shoes. But in a sprint, dependent as it is on raw power, one of the biggest single contributors to victory is physiological: the muscle fibers in Greene's legs, particularly his thighs, are able to generate slightly more power for the brief duration of the sprint than can those of his competitors.

Recent findings in our laboratories and elsewhere have expanded our knowledge of how human muscle adapts to exercise or the lack of it and the extent to which an individual's muscle can alter itself to meet different challenges - such as the long struggle of a marathon or the explosive burst of a sprint. The information helps us understand why an athlete like Greene triumphs and also gives us insights into the range of capabilities of ordinary people. It even sheds light on the perennial issue of whether elite runners, swimmers, cyclists and cross-country skiers are born different from the rest of us or whether proper training and determination could turn almost anyone into a champion.

Skeletal muscle is the most abundant tissue in the human body and also one of the most adaptable. Vigorous training with weights can double or triple a muscle's size, whereas disuse, as in space travel, can shrink it by 20 percent in two weeks. The many biomechanical and biochemical phenomena behind these adaptations are enormously complex, but decades of research have built up a reasonably complete picture of how muscles respond to athletic training.

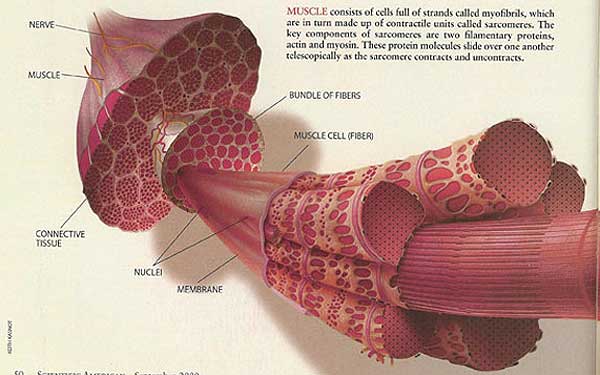

What most people think of as a muscle is actually a bundle of cells, also known as fibers, kept together by collagen tissue. A single fiber of skeletal muscle consists of a membrane, many scattered nuclei that contain the genes and lie just under the membrane along the length of the fiber, and thousands of inner strands called myofibrils that constitute the cytoplasm of the cell. The largest and longest human muscle fibers are up to 30 centimeters long and 0.05 to 0.15 millimeter wide and contain several thousand nuclei.

Filling the inside of a muscle fiber, the myofibrils are the same length as the fiber and are the part that causes the cell to contract forcefully in response to nerve impulses. Motor nerve cells, or neurons, extend from the spinal cord to a group of fibers, making up a motor unit. In leg muscles, a motor neuron controls, or "innervates," several hundred to 1,000 or more muscle fibers. Where extreme precision is needed, for example, to control a finger, an eyeball or the larynx, one motor neuron controls only one or at most a few muscle fibers.

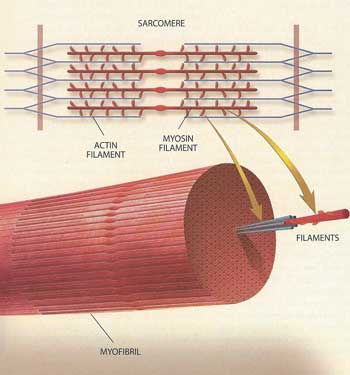

The actual contraction of a myofibril is accomplished by its tiny component units, which are called sarcomeres and are linked end to end to make up a myofibril. Within each sarcomere are two filamentary proteins, known as myosin and actin, whose interaction causes the contraction. Basically, during contraction a sarcomere shortens like a collapsing telescope, as the actin filaments at each end of a central myosin filament slide toward the myosin's center.

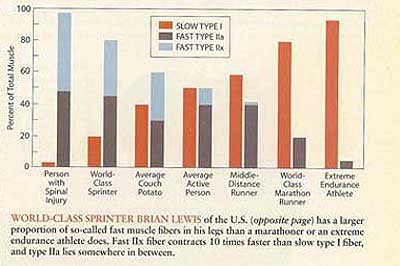

One component of the myosin molecule, the so-called heavy chain, determines the functional characteristics of the muscle fiber. In an adult, this heavy chain exists in three different varieties, known as isoforms. These isoforms are designated I, IIa and IIx, as are the fibers that contain them. Type I fibers are also known as slow fibers; type IIa and IIx are referred to as fast fibers. The fibers are called slow and fast for good reason: the maximum contraction velocity of a single type I fiber is approximately one tenth that of a type IIx fiber. The velocity of type IIa fibers is somewhere between those of type I and type IIx.

The Stuff of Muscle

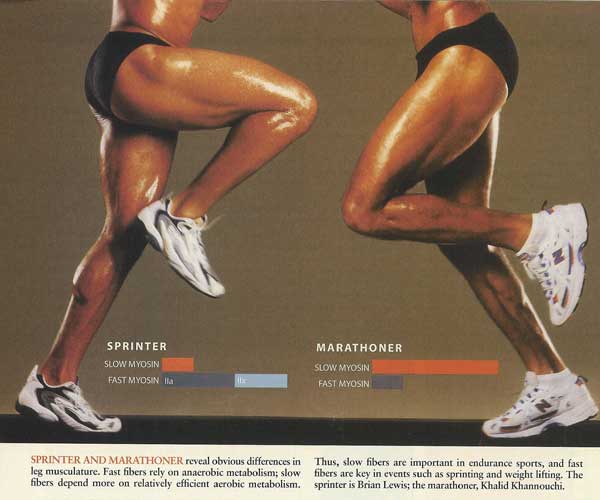

The differing contraction speeds of the fibers is a result of differences in the way the fibers break down a molecule called adenosine triphosphate in the myosin heavy chain region to derive the energy needed for contraction. Slow fibers rely more on relatively efficient aerobic metabolism, whereas the fast fibers depend more on anaerobic metabolism. Thus, slow fibers are important for endurance activities and sports such as long-distance running, cycling and swimming, whereas fast fibers are key to power pursuits such as weight lifting and sprinting.

The "average" healthy adult has roughly equal numbers of slow and fast fibers in, say, the quadriceps muscle in the thigh. But as a species, humans show great variation in this regard; we have encountered people with a slow fiber percentage as low as 19 percent and as high as 95 percent in the quadriceps muscle. A person with 95 percent slow fibers could probably become an accomplished marathoner but would never get anywhere as a sprinter; the opposite would be true of a person with 19 percent slow fibers.

>Besides the three distinct fiber types, there are hybrids containing two different myosin isoforms. The hybrid fibers fall in a continuum ranging from those almost totally dominated by, say, the slow isoform to fibers almost totally dominated by a fast one. In either case, as might be expected, the functional characteristics of the fiber are close to those of the dominant fiber type.

Myosin is an unusual and intriguing protein. Comparing myosin isoforms from different mammals, researchers have found remarkably little variation from species to species. The slow (type 1) myosin found in a rat is much more similar to the slow isoform found in humans than it is to the rat's own fast myosins. This fact suggests that selective evolutionary pressure has maintained functionally distinct myosin isoforms and that this pressure has basically preserved particular isoforms that came about over millions of years of evolution. These myosin types arose quite early in evolution-even the most ancient and primitive creatures had myosin isoforms not terribly different from ours.

Bulking Up

Muscle fibers cannot split themselves to form completely new fibers. As people age, they lose muscle fibers, but they never gain new ones. So a muscle can become more massive only when its individual fibers become thicker.

What causes this thickening is the creation of additional myofibrils. The mechanical stresses that exercise exerts on tendons and other structures connected to the muscle trigger signaling proteins that activate genes that cause the muscle fibers to make more contractile proteins. These proteins, chiefly myosin and actin, are needed as the fiber produces great amounts of additional myofibrils.

More nuclei are required to produce and support the making of additional protein and to keep up a certain ratio of cell volume to nuclei. As mentioned, muscle fibers have multiple nuclei, but the nuclei within the muscle fiber cannot divide, so the new nuclei are donated by so-called satellite cells (also known as stem cells). Scattered among the many nuclei on the surface of a skeletal muscle fiber, satellite cells are largely separate from the muscle cell. The satellite cells have only one nucleus apiece and can replicate by dividing. After fusion with the muscle fiber, they serve as a source of new nuclei to supplement the growing fiber.

Satellite cells proliferate in response to the wear and tear of exercise. One theory holds that rigorous exercise inflicts tiny "microtears" in muscle fibers. The damaged area attracts the satellite cells, which incorporate themselves into the muscle tissue and begin producing proteins to fill the gap. As the satellite cells multiply, some remain as satellites on the fiber, but others become incorporated into it. These nuclei become indistinguishable from the muscle cell's other nuclei. With these additional nuclei, the fiber is able to churn out more proteins and create more myofibrils.

To produce a protein, a muscle cell like any cell in the body-must have a "blueprint" to specify the order in which amino acids should be put together to make the protein - in other words, to indicate which protein will be created. This blueprint is a gene in the cell's nucleus, and the process by which the information gets out of the nucleus into the cytoplasm, where the protein will be made, starts with transcription. It occurs in the nucleus when a gene's information (encoded in DNA) is copied into a molecule called messenger RNA. The mRNA then carries this information outside the nucleus to the ribosomes, which assemble amino acids into the proteins - actin or one of the myosin isoforms, for example-as specified by the mRNA. This last process is called translation. Biologists refer to the entire process of producing a protein from a gene as "expression" of that gene.

Two of the most fundamental areas of study in skeletal muscle research ones that bear directly on athletic performance - revolve around the way in which exercise and other stimuli cause muscles to become enlarged (a process called hypertrophy) and how such activity can convert muscle fibers from one type to another. We and others have pursued these subjects intensively in recent years and have made some significant observations.

The research goes back to the early 1960s, when A. J. Buller and John Carew Eccles of the Australian National University in Canberra and later Michael Barany and his co-workers at the Institute for Muscle Disease in New York City performed a series of animal studies that converted skeletal muscle fibers from fast to slow and from slow to fast. The researchers used several different means to convert the fibers, the most common of which was cross-innervation. They switched a nerve that controlled a slow muscle with one linked to a fast muscle, so that each controlled the opposite type of fiber. The researchers also electrically stimulated muscles for prolonged periods or, to get the opposite effect, cut the nerve leading to the muscle.

In the 1970s and 1980s muscle specialists focused on demonstrating that the ability of a muscle fiber to change size and type, a feature generally referred to as muscle plasticity, also applied to humans. An extreme example of this effect occurs in people who have suffered a spinal cord injury serious enough to have paralyzed their lower body. The lack of nerve impulses and general disuse of the muscle cause a tremendous loss of tissue, as might be expected. More surprisingly, the type of muscle changes dramatically. These paralyzed subjects experience a sharp decrease of the relative amount of the slow myosin isoform, whereas the amount of the fast myosin isoforms actually increases.

We have shown that many of these subjects have almost no slow myosin in their vastus lateralis muscle, which is part of the quadriceps in the thigh, after five to 10 years of paralysis; essentially all myosin in this muscle is of the fast type. Recall that in the average healthy adult the distribution is about 50-50 for slow and fast fibers. We hypothesized that the neural input to the muscle, by electrical activation, is necessary for maintaining the expression of the slow myosin isoform. Thus, electrical stimulation or electrically induced exercise of these subjects' muscles can, to some extent, reintroduce the slow myosin in the paralyzed muscles.

Converting Muscle

Conversion of muscle fibers is not limited to the extreme case of the reconditioning of paralyzed muscle. In fact, when healthy muscles are loaded heavily and repeatedly, as in a weight training program, the number of fast IIx fibers declines as they convert to fast IIa fibers. In those fibers the nuclei stop expressing the IIx gene and begin expressing the IIa. If the vigorous exercise continues for about a month or more, the IN muscle fibers will completely transform to Ila fibers. At the same time, the fibers increase their production of proteins, becoming thicker.

In the early 1990s Geoffrey Goldspink of the Royal Free Hospital in London suggested that the fast IIx gene constitutes a kind of "default" setting. This hypothesis has held up in various studies over the years that have found that sedentary people have higher amounts of myosin IN in their muscles than do fit, active people. Moreover, complementary studies have found a positive correlation between myosin IIa and muscle activity.

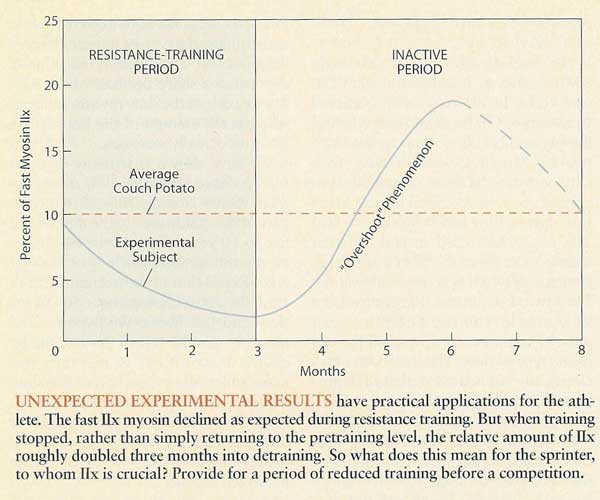

What happens when exercise stops? Do the additional IIa fibers then convert back to IIx? The answer is yes, but not in the precise manner that might be expected. To study this issue, we took muscle samples (biopsies) from the vastus lateralis muscle of nine young, sedentary Danish men. We then had the subjects conduct heavy resistance training, aimed mainly at their quadriceps muscle, for three months, ending with another muscle biopsy. Then the subjects abruptly stopped the resistance training and returned to their sedentary lifestyle, before being biopsied for a third and final time after a three-month period of inactivity (corresponding to their behavior prior to entering the training).

As expected, the relative amount of the fast myosin IIx isoform in their vastus lateralis muscle was reduced from an average of 9 percent to about 2 percent in the resistance-training period. We then expected that the relative amount of the IN isoform would simply return to the pretraining level of 9 percent during the period of inactivity. Much to our surprise, the relative amount of myosin IIx reached an average value of 18 percent three months into the detraining. We did not continue the biopsies after the three-month period, but we strongly suspect that the myosin lIx did eventually return to its initial value of about 9 percent some months later.

We do not yet have a good explanation for this "overshoot" phenomenon of the expression of the fast myosin IIx isoform. Nevertheless, we can draw some conclusions that can have useful applications. For instance, if sprinters want to boost the relative amount of the fastest fibers in their muscles, the best strategy would be to start by removing those that they already have and then slow down the training and wait for the fastest fibers to return twofold! Thus, sprinters would be well advised to provide in their schedule for a period of reduced training, or "tapering," leading up to a major competition. In fact, many sprinters have settled on such a regimen simply through experience, without understanding the underlying physiology.

Slow to Fast?

Conversion between the two fast fiber types, IIa and IN, is a natural consequence of training and detraining. But what about conversion between the slow and fast fibers, types I and II? 1 Here the results have been somewhat murkier. Man\, experiments performed over the past couple of decades found no evidence that slow fibers can he converted to fast, and vice versa. But in the early 1990s we did get an indication that a rigorous exercise regimen could convert slow fibers to fast IIa fibers.

Our subjects were very elite sprinters, whom we studied during a three-month period in which they combined heavy resistance training with short-interval running (these are the foundation exercises in a sprinter's yearly training cycle). At around the same time, Mona Esbornsson and her co-workers at the Karohnska Institute in Stockholm reported similar findings in a study involving a dozen subjects who were not elite athletes. These results suggest that a program of vigorous weight training supplemented with other forms of anaerobic exercise converts not only type IIx fibers to IIa but also type I fibers to IIa. If a certain type of exertion can convert some type I fibers to Ila, we might naturally wonder if some other kind can convert IIa to I. It may be possible, but so far no lengthy human training study has unambiguously demonstrated such a shift. True, star endurance athletes such as long-distance runners and swimmers, cyclists and cross-country skiers generally have remarkably high proportions - up to 95 percent, as mentioned earlier - of the slow type 1 fibers in their major muscle groups, such as the legs. Yet at present we do not know whether these athletes were born with such a high percentage of type I fibers and gravitated toward sports that take advantage of their unusual inborn trait or whether they very gradually increased the proportion of type I fibers in their muscles as they trained over a period of many months or years. We do know that if fast type IIa fibers can be converted to type I, the time required for the conversion is quite long in comparison with the time for the shift from IIx to Ila.

It may be that great marathon runners are literally born different from other people. Sprinters, too, might be congenitally unusual: in contrast with long-distance runners, they of course would benefit from a relatively small percentage of type I fibers. Still, a would-be sprinter with too many type I fibers need not give up. Researchers have found that hypertrophy from resistance training enlarges type 11 fibers twice as much as it does type I fibers. Thus, weight training can increase the cross-sectional area of the muscle covered by fast fibers without changing the relative ratio between the number of slow and fast fibers in the muscle. Moreover, it is the relative crosssectional area of the fast and slow fibers that determines the functional characteristics of the entire muscle. The more area covered by fast fibers, the faster the overall muscle will be. So a sprinter at least has the option of altering the characteristics of his or her leg muscles by exercising them with weights to increase the relative cross section of fast fibers.

In a study published in 1988 Michael Sjostrom and his co-workers at the University of Umea, Sweden, disclosed their finding that the average cross-sectional areas of the three main fiber types were almost identical in the vastus lateralis muscles of a group of marathon runners. In those subjects the cross-sectional area of type I fibers averaged 4,800 square microns; type IIa was 4,500; and type IIx was 4,600. For a group of sprinters, on the other hand, the average fiber sizes varied considerably: the type I fibers averaged 5,000 square microns; type IIa, 7,300; and type IIx, 5,900. We have results from a group of sprinters that are very similar.

Although certain types of fiber conversion, such as IIa to I, appear to be difficult to bring about through exercise, the time is fast approaching when researchers will be able to accomplish such conversions easily enough through genetic techniques. Even more intriguing, scientists will be able to trigger the expression of myosin genes that exist in the genome but are not normally expressed in human muscles. These genes are like archival blueprints for myosin types that might have endowed ancient mammalian relatives of ours with very fast muscle tissue that helped them escape predators, for example.

Such genetic manipulations, most likely in the form of vaccines that insert artificial genes into the nuclei of muscle cells, will almost certainly be the performanceenhancing drugs of the future. Throughout the recorded history of sports a persistent minority of athletes have abused performance-enhancing substances. Organizations such as the International Olympic Committee have for decades tried to suppress these drugs by testing athletes and censuring those found to have cheated. But as soon as new drugs are invented, they are co-opted by dishonest athletes, forcing officials to develop new tests. The result has been an expensive race pitting the athletes and their "doctors" against the various athletic organizations and the scientists developing new antidoping tests.

This contest is ongoing even now in Sydney, but within the near future, when athletes can avail themselves of gene therapy techniques, they will have taken the game to a whole new level. The tiny snippets of genetic material and the proteins that gene therapy will leave behind in the athletes' muscle cells may be impossible to identify as foreign.

Gene therapy is now being researched intensively in most developed countries for a host of very good reasons. Instead of treating deficiencies by injecting drugs, doctors will be able to prescribe genetic treatments that will induce the body's own protein-making machinery to produce the proteins needed to combat illness. Such strategies became possible, at least in theory, in recent years as researchers succeeded in making artificial copies of the human genes that could be manipulated to produce large amounts of specific proteins. Such genes can be introduced into the human body where, in many cases, they substitute for a defective gene.

Like ordinary genes, the artificial gene consists of DNA. It can be delivered to the body in several ways. Suppose the gene encodes for one of the many signaling proteins or hormones that stimulate muscle growth. The direct approach would be to inject the DNA into the muscle. The muscle fibers would then take up the DNA and add it to the normal pool of genes. This method is not very efficient yet, so researchers often use viruses to carry the gene payload into a cell's nuclei. A virus is essentially a collection of genes packed in a protein capsule that is able to bind to a cell and inject the genes. Scientists replace the virus's own genes with the artificial gene, which the virus will then efficiently deliver to cells in the body.

Unfortunately, and in contrast to the direct injection of DNA, the artificial gene payload will be delivered not only to the muscle fibers but also to many other cells, such as those of the blood and the liver. Undesirable side effects could very well occur when the artificial gene is expressed in cell types other than the targeted ones. For example, if a gene causing extended muscle hypertrophy were injected, this would lead to the desired growth of the skeletal muscles. But it would probably also lead to hypertrophy of another kind of muscle, namely that of the heart, giving rise to all the well-known complications of having an enlarged heart. So researchers have explored another approach, which entails removing specific cell types from the patient, adding the artificial gene in the laboratory and reintroducing the cells into the body.

These techniques will be abused by athletes in the future. And sports officials will be hard-pressed to detect the abuse, because the artificial genes will produce proteins that in many cases are identical to the normal proteins. Furthermore, only one injection will be needed, minimizing the risk of disclosure. It is true that officials will be able to detect the DNA of the artificial gene itself, but to do so they would have to know the sequence of the artificial gene, and the testers would have to obtain a sample of the tissue containing the DNA. Athletes, of course, will be quite reluctant to surrender muscle samples before an important competition. Thus, a doping test based on taking pieces of the athletes' muscle is not likely to become routine. For all intents and purposes, gene doping will be undetectable.

Brave New World

What will athletics be like in an age of genetic enhancements? Let us reconsider our opening scenario, at the men's 100-meter final. Only this time it is the year 2012. Prior to these Olympics, it was hard to pick an obvious favorite for the gold medal. After the preliminary heats, that is not so anymore. Already after the semifinals the bookmakers closed the bets for the runner in lane four, John Doeson. He impressed everyone by easing through his 1/8 final in a time only 3/100 of a second from the now eight-year-old world record. In the quarterfinal he broke the world record by 15/100 of a second, but the 87,000 spectators did not believe their eyes when in the semifinals he lowered the world record to an unbelievable 8.94 seconds, passing the finish line more than 10 meters ahead of the secondplace runner. This performance made several television commentators maintain that the viewers had just seen "something from out of this world."

Not quite, but close. What could have led to such an astonishing performance? By 2012 gene therapy will probably be a well-established and widely used medical technology. Let us say that 12 months before the Olympics, a doctor approached Doeson with a proposal likely to sorely tempt any sprinter. What if you could make your muscle cells express the fastest myosin isoform? Under normal conditions, this isoform is not expressed in any of the major human skeletal muscles, but the gene is there and ready to work, like a dusty blueprint that just needs a civil engineer and a construction crew to make it a reality.

This enticing myosin isoform would give muscle fibers functional characteristics that correspond to those of the very fast IIb isoform, found in the rat and in other small mammals that need bursts of speed to elude predators. This IIb isoform has a much higher velocity of contraction and so can generate more power than IIx or Ila fibers. Although Doeson didn't really understand what the doctor was talking about, he fully understood the words "velocity" and "power."

The doctor enthusiastically went on explaining his idea. The gene actually expresses a kind of protein known as a transcription factor, which in turn activates the gene for the very fast myosin IIb isoform. Such a transcription factor was discovered a few years ago and was named Velociphin. Holding a tiny glass vial in front of Doeson's face, he intoned: "This is the DNA for an artificial gene for Velociphin. Just a few injections of this DNA into your quadriceps, hamstring and gluteus, and your muscle fibers will start cranking out Velociphin, which will activate the myosin IIb gene."

Within three months, he added, Doeson's muscles would contain a good portion of IIb fibers, enabling him to break the 100-meter world record with ease. Moreover, the doctor noted, Doeson's muscles would keep producing Velociphin for years without further injections. And without a muscle biopsy from the quadriceps, hamstring or gluteus, there will be no way for officials to detect the genetic modification.

A year later, as he pulls on his track suit, Doeson recalls the doctor's assurance that there would be no side effects of the genetic treatment. So far, so good. After stretching and warming up, he takes his place on the block in lane four. "On your mark. Get set. BANG!" The runners are away.

A couple of seconds later Doeson is already ahead by two meters. Over the next few seconds, astonishingly, his lead grows. In comparison with those of the other runners, his strides are visibly more powerful and frequent. He feels good as he passes 30, 40 and 50 meters. But then, at 65 meters, far out in front of the field, he feels a sudden twinge in his hamstring. At 80 meters the twinge explodes into overwhelming pain as he pulls his hamstring muscle. A tenth of a second later Doeson's patella tendon gives in, because it is no match for the massive forces generated by his quadriceps muscle. The patella tendon pulls out part of the tibia bone, which then snaps, and the entire quadriceps shoots up along the femur bone. Doeson crumples to the ground, his running career over.

That is not the scenario that generally springs to mind in connection with the words "genetically engineered superathlete." And some athletes will probably manage to exploit engineered genes while avoiding catastrophe. But it is clear that as genetic technologies begin trickling into the mainstream of medicine they will change sports profoundly - and not for the better. As a society, we will have to ask ourselves whether new records and other athletic triumphs really are a simple continuation of the age-old quest to show what our species can do.

The Authors

Further Information

JESPER L. ANDERSEN, PETER SCHJERLING and BENGT SALTIN work together at the Copenhagen Muscle Research Center, which is affiliated with the University of Copenhagen and the city's University Hospital. Andersen is a researcher in the department of molecular muscle biology and a former coach of the sprint team of the Danish national track-and-field team. Schjerling, a geneticist in the same department, recently changed his area of specialty from yeast to a considerably more muscular creature, Homo sapiens. Saltin, director of the center, graduated from the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm in 1964 and worked as a professor of human physiology there and at the University of Copenhagen's August Krogh Institute. A former competitive runner, he has also coached the Danish national orienteering team.

THE CYTOSKELETON in Molecular Biology o f the Cell. Bruce Alberts et al. Third edition. Garland Publishing, 1994.

MUSCULAR AGAIN. Glenn Zorpette in SCIENTIFIC AMERICAN PRESENTS: Your Bionic Future, Vol. 10, No. 3, pages 27-31, Fall 1999.

THE MYSTERY of MUSCLE. Glenn Zorpette in SCIENTIFIC AMERICAN PRESENTS: Men-The Scientific Truth, Vol. 10, No. 2, pages 48-55, Summer 1999.

Muscle, Genes and Athletic Performance SCIENTIFIC AMERICAN September 2000 55